values <- 1:10

# Vectorized

sum(values)[1] 55Briefly go over the bigger picture (found in the introduction section) and remind everyone the ‘what’ and ‘why’ of what we are doing.

Time: ~6 minutes.

A very effective way to learn is to recall and describe to someone else what you’ve learned. So before we continue this session, take some time to think about what you’ve learned from yesterday.

Go over this section briefly by reinforcing what they read, especially reinforcing the concepts shown in the image. Make sure they understand the concept of applying something to many things at once and that functionals are better coding patterns to use compared to loops. Doing the code-along should also help reinforce this concept.

Also highlight that the resources appendix has some links for continued learning for this and that the Posit purrr cheat sheet is an amazing resource to use.

Time: ~10 minutes.

Unlike many other programming languages, R’s primary strength and approach to programming is in functional programming. So what is “functional programming”? At its simplest, functional programming is a way of thinking about and doing programming that is declarative rather than imperative. A functional (“declarative”) way of thinking is actually how we humans intuitively think about the world. Unfortunately, many programming languages are imperative, and even the computer at its core needs imperative instructions. This is part of the reason why programming is so hard for humans.

A useful analogy is that functional programming is like how you talk to an adult about what you want done and letting the adult do it, e.g. “move these chairs to this room”. “Imperative” is how you’d talk to a very young child to make sure it is done exactly as you say, without deviations from those instructions. Using the chair example, it would be like saying “take this chair, walk over to that room, drop of the chair in the corner, come back, take that next chair, walk back to the room and put it beside the other chair, …” and so on. There’s a lot of room for error because, e.g. “take” or “walk” or “drop” can mean many different things.

Functional programming, in R, is programming that:

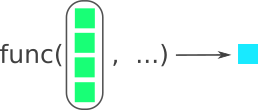

function()).We’ve already covered functions. You’ve definitely already used vectorization since it is one of R’s big strengths. For instance, functions like mean(), sd(), or sum() are vectorized in that you give them a vector of numbers and they do something to all the values in the vector at once. In vectorized functions, you can give the function an entire vector (e.g. c(1, 2, 3, 4)) and R will know what to do with it. Figure 8.1 shows how a function conceptually uses vectorization.

func() function and outputs a single item on the right. Modified from the Posit purrr cheat sheet. Image license is CC-BY-SA 4.0.

For example, in R, there is a vectorized function called sum() that takes the entire vector of values and outputs the total sum.

values <- 1:10

# Vectorized

sum(values)[1] 55In many other programming languages, you would need to use a loop to calculate the sum because the language doesn’t support vectorization. In R, a loop to calculate the sum would look like this:

total_sum <- 0

# a vector

values <- 1:10

for (value in values) {

total_sum <- value + total_sum

}

total_sum[1] 55Emphasize this next paragraph.

Writing effective and correct loops is surprisingly difficult and tricky. Because of this and because there are better and easier ways of writing R code to replace loops, we strongly recommend not using loops. If you think you need to, you probably don’t. This is why we will not be covering loops in this workshop.

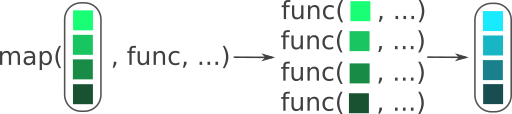

A functional is R’s native way of doing loops. A functional is a function where you give it a function as one of its arguments. Figure 8.2 shows how the functional map() from the purrr package works by taking a vector (or list), applying a function to each of those items, and outputting the results from each function. The name map() doesn’t mean a geographic map, it is the mathematical meaning of map: To use a function on each item in a set of items.

map(), applies a function to each item in a vector. Notice how each of the green coloured boxes are placed into the func() function and outputs the same number of blue boxes as there are green boxes. Modified from the Posit purrr cheat sheet. Image license is CC-BY-SA 4.0.

Here’s a simple example to show how it works. We’ll use paste() on each item of 1:5 to simple output the same number as the input. We will load in purrr to be clear which package it comes from, but purrr is loaded with the tidyverse package, so you don’t need to load it if you are using the tidyverse package.

[[1]]

[1] "1"

[[2]]

[1] "2"

[[3]]

[1] "3"

[[4]]

[1] "4"

[[5]]

[1] "5"You’ll notice that map() outputs a list, with all the [[1]] printed. A list is a specific type of object that can contain different types of objects. For example, a data frame is actually a special type of list where each column is a list item that contains the values of that column. map() will always output a list, so it is very predictable. Notice also that the paste() function is given without the () brackets. Without the brackets, the function can be used by the map() functional and treated like any other object in R. Remember how we said that a function is an action when it has () at the end. In this case, we do not want R to do the action yet, we want R to use the action on each item in the map(). In order for map() to do that, you need to give the function as an object so it can do the action later.

Let’s say we wanted to paste together the number with the sentence “seconds have passed”. Normally it would look like:

paste(1, "seconds have passed")[1] "1 seconds have passed"paste(2, "seconds have passed")[1] "2 seconds have passed"paste(3, "seconds have passed")[1] "3 seconds have passed"paste(4, "seconds have passed")[1] "4 seconds have passed"paste(5, "seconds have passed")[1] "5 seconds have passed"Or as a loop:

[1] "1 seconds have passed"

[1] "2 seconds have passed"

[1] "3 seconds have passed"

[1] "4 seconds have passed"

[1] "5 seconds have passed"Using map() we can give it something called “anonymous” functions. “Anonymous” because it isn’t named with name <- function() like we’ve done before. Anonymous functions are functions that you use once and don’t remember in your environment (like named functions do). As you might guess, you can make an anonymous function by simply not naming it! For instance:

function(number) {

paste(number, "seconds have passed")

}There is a shortened version of this using \(x):

\(number) paste(number, "seconds have passed")Both forms of anonymous functions are equivalent and can be used in map():

[[1]]

[1] "1 seconds have passed"

[[2]]

[1] "2 seconds have passed"

[[3]]

[1] "3 seconds have passed"

[[4]]

[1] "4 seconds have passed"

[[5]]

[1] "5 seconds have passed"[[1]]

[1] "1 seconds have passed"

[[2]]

[1] "2 seconds have passed"

[[3]]

[1] "3 seconds have passed"

[[4]]

[1] "4 seconds have passed"

[[5]]

[1] "5 seconds have passed"So map() will take each number in 1:5, put it into the anonymous function in the number argument we made, and then run the paste() function on it. The output will be a list of the results of the paste() function.

purrr also supports the use of a syntax shortcut to write anonymous functions. This shortcut is using ~ (tilde) to start the function and .x as the replacement for the vector item. .x is used instead of x in order to avoid potential name collisions in functions where x is an function argument (for example in ggplot2::aes(), where x can be used to define the x-axis mapping for a graph). Here is the same example as above, now using the ~ shortcut:

[[1]]

[1] "1 seconds have passed"

[[2]]

[1] "2 seconds have passed"

[[3]]

[1] "3 seconds have passed"

[[4]]

[1] "4 seconds have passed"

[[5]]

[1] "5 seconds have passed"The ~ was made before \() was made in R. After this new, native R version was made, the purrr authors now strongly recommend using it rather then their ~ for anonymous functions. The \() is also a bit clearer because you give it the name of the argument, e.g. number, rather than be forced to use .x.

map() will always output a list, but sometimes we might want to output a different data type. If we look into the help documentation with ?map, it shows several other types of map that all start with map_:

map_chr() outputs a character vector.map_int() outputs an integer vector.map_dbl() outputs a numeric value, called a “double” in programming.This is the basics of functionals like map(). Functions, vectorization, and functionals provide expressive and powerful approaches to a simple task: Doing an action on each item in a set of items. And while technically using a for loop lets you “not repeat yourself”, they tend to be more error prone and harder to write and read compared to these other tools. For some alternative explanations of this, see Section A.2.

When you’re ready to continue, place the sticky/paper hat on your computer to indicate this to the teacher 👒 🎩

But what does functionals have to do with what we are doing now? Well, we have the import_dime() that only imports one CSV file. But we have many more! Well, we can use functionals to import them all at once 😁

Before we can use map() though, we need to have a vector or list of the file paths for all the CSV files we want to import. For that, we can use the fs package, which has a function called dir_ls() that finds files in a folder (directory).

So, let’s add library(fs) to the setup code chunk. Then, go to the bottom of the docs/learning.qmd document, create a new header called ## Using map, and create a code chunk below that with Ctrl-Alt-ICtrl-Alt-I or with the Palette (Ctrl-Shift-PCtrl-Shift-P, then type “new chunk”)

The dir_ls() function takes the path that we want to search, in this case data-raw/dime/cgm and has an argument called glob to tell it what type of files to search for. In our case, we want to search for all CSV files in the data-raw/dime/cgm/ folder. So we will pipe the output of the path to the CGM folder with here() into dir_ls():

Then we can see what the output is. The paths you see on your computer will be different from what are shown here (it is a different computer). Plus to keep it simpler, on the website we will only show the first 6 files.

docs/learning.qmd

cgm_filesdata-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv data-raw/dime/cgm/102.csv

data-raw/dime/cgm/104.csv Alright, we now have all the files ready to give to map().

docs/learning.qmd

cgm_data <- cgm_files |>

map(import_dime)Remember, that map() always outputs a list, so when we look into this object, it will give us 19 tibbles (data frames). For the website we’ll only show the first two tibbles:

docs/learning.qmd

cgm_data[1:2]$`/home/runner/work/r-cubed-intermediate/r-cubed-intermediate/data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv`

# A tibble: 100 × 2

device_timestamp historic_glucose_mmol_l

<dttm> <dbl>

1 2021-03-18 08:15:00 5.8

2 2021-03-18 08:30:00 5.4

3 2021-03-18 08:45:00 5.1

4 2021-03-18 09:01:00 5.3

5 2021-03-18 09:16:00 5.3

6 2021-03-18 09:31:00 4.9

7 2021-03-18 09:46:00 4.7

8 2021-03-18 10:01:00 4.8

9 2021-03-18 10:16:00 5.5

10 2021-03-18 10:31:00 5.7

# ℹ 90 more rows

$`/home/runner/work/r-cubed-intermediate/r-cubed-intermediate/data-raw/dime/cgm/102.csv`

# A tibble: 100 × 2

device_timestamp historic_glucose_mmol_l

<dttm> <dbl>

1 2021-03-19 09:02:00 2.2

2 2021-03-19 09:17:00 2.2

3 2021-03-19 09:32:00 2.2

4 2021-03-19 09:46:00 2.2

5 2021-03-19 17:29:00 5.1

6 2021-03-19 17:44:00 4.7

7 2021-03-19 17:59:00 4.9

8 2021-03-19 18:14:00 5.6

9 2021-03-19 18:29:00 5.9

10 2021-03-19 18:45:00 6.2

# ℹ 90 more rowsRemind everyone that we still only import the first 100 rows of each data file. So if some of the data itself seems looks odd or so little data, that is the reason why. Remind them that we do this to more quickly prototype and test code out.

This is great because with one line of code we imported all these datasets and made them into one data frame! But we’re missing an important bit of information: The participant ID. The purrr package has many other powerful functions to make it easier to work with functionals. We know map() always outputs a list. But what we want is a single tibble at the end that also contains the participant ID.

There are two functions that take a list of data frames and convert them into a single data frame. They are called list_rbind() to bind (“stack”) the data frames by rows or list_cbind() to bind (“stack”) the data frames by columns. In our case, we want to bind (stack) by rows, so we will use list_rbind() by piping the output of the map() code we wrote into list_rbind().

docs/learning.qmd

cgm_data <- cgm_files |>

map(import_dime) |>

list_rbind()

cgm_data# A tibble: 1,900 × 2

device_timestamp historic_glucose_mmol_l

<dttm> <dbl>

1 2021-03-18 08:15:00 5.8

2 2021-03-18 08:30:00 5.4

3 2021-03-18 08:45:00 5.1

4 2021-03-18 09:01:00 5.3

5 2021-03-18 09:16:00 5.3

6 2021-03-18 09:31:00 4.9

7 2021-03-18 09:46:00 4.7

8 2021-03-18 10:01:00 4.8

9 2021-03-18 10:16:00 5.5

10 2021-03-18 10:31:00 5.7

# ℹ 1,890 more rowsBut, hmm, we don’t have the participant ID in the data frame. This is because list_rbind() doesn’t know how to get that information, since it isn’t included in the data frames. If we look at the help for list_rbind(), we will see that it has an argument called names_to. This argument lets us create a new column that is based on the name of the list item, which in our case is the file path. This file path also has the participant ID information in it, but it also has the full file path in it too, which isn’t exactly what we want. So we’ll have to fix it later. But first, let’s start with adding this information to the data frame as a new column called file_path_id. So we will add the names_to argument to the code we’ve already written.

docs/learning.qmd

cgm_data <- cgm_files |>

map(import_dime) |>

list_rbind(names_to = "file_path_id")And then look at it by running cgm_data below the code:

docs/learning.qmd

cgm_data# A tibble: 1,900 × 3

file_path_id device_timestamp historic_glucose_mmol_l

<chr> <dttm> <dbl>

1 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 08:15:00 5.8

2 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 08:30:00 5.4

3 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 08:45:00 5.1

4 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 09:01:00 5.3

5 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 09:16:00 5.3

6 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 09:31:00 4.9

7 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 09:46:00 4.7

8 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 10:01:00 4.8

9 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 10:16:00 5.5

10 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 10:31:00 5.7

# ℹ 1,890 more rowsThe file_path_id variable will look different on everyone’s computer. Don’t worry, we’re going to tidy up the file_path_id variable later in another session.

Before moving on to the exercise, let’s style with the Palette (Ctrl-Shift-PCtrl-Shift-P, then type “style file”) the document, render with Ctrl-Shift-KCtrl-Shift-K or with the Palette (Ctrl-Shift-PCtrl-Shift-P, then type “render”), and finally add and commit the changes to the Git history using Ctrl-Alt-MCtrl-Alt-M or with the Palette (Ctrl-Shift-PCtrl-Shift-P, then type “commit”) before pushing to GitHub.

Because later sessions depend on this code, after they’ve finished the exercise, walk through with them the solution. So that we are all on the same page.

Time: ~20 minutes.

We’ve made some code that does what we want, now the next step is to convert it into a function so we can use it on both the cgm and sleep datasets. The code we’ve written to import only the cgm data looks like this:

cgm_files <- here("data-raw/dime/cgm/") |>

dir_ls(glob = "*.csv")

cgm_data <- cgm_files |>

map(import_dime) |>

list_rbind(names_to = "file_path_id")

cgm_dataWe want to be able to do the same thing for the sleep data, but we don’t want to repeat ourselves. What we want is a new function that looks like the code chunk below and that outputs a similar data frame, though the file_path_id values will be different:

# A tibble: 1,900 × 3

file_path_id device_timestamp historic_glucose_mmol_l

<chr> <dttm> <dbl>

1 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 08:15:00 5.8

2 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 08:30:00 5.4

3 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 08:45:00 5.1

4 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 09:01:00 5.3

5 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 09:16:00 5.3

6 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 09:31:00 4.9

7 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 09:46:00 4.7

8 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 10:01:00 4.8

9 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 10:16:00 5.5

10 data-raw/dime/cgm/101.csv 2021-03-18 10:31:00 5.7

# ℹ 1,890 more rows# A tibble: 1,800 × 4

file_path_id date sleep_type seconds

<chr> <dttm> <chr> <dbl>

1 data-raw/dime/sleep/101.csv 2021-05-24 23:03:00 wake 540

2 data-raw/dime/sleep/101.csv 2021-05-24 23:12:00 light 180

3 data-raw/dime/sleep/101.csv 2021-05-24 23:15:00 deep 1440

4 data-raw/dime/sleep/101.csv 2021-05-24 23:39:00 light 240

5 data-raw/dime/sleep/101.csv 2021-05-24 23:43:00 wake 300

6 data-raw/dime/sleep/101.csv 2021-05-24 23:48:00 light 120

7 data-raw/dime/sleep/101.csv 2021-05-24 23:50:00 rem 1350

8 data-raw/dime/sleep/101.csv 2021-05-25 00:12:30 wake 870

9 data-raw/dime/sleep/101.csv 2021-05-25 00:27:00 rem 360

10 data-raw/dime/sleep/101.csv 2021-05-25 00:33:00 light 210

# ℹ 1,790 more rowsComplete the tasks below to convert this code into a stable, robust function that you can re-use.

DESCRIPTION file by using usethis::use_package() in the Console.docs/learning.qmd, create a new header ## Exercise: Convert map to function and use on sleep.import_csv_files.function() { ... } code to create a new functionfunction(), add an argument called folder_path.here("data-raw/dime/cgm") with folder_path.cgm_files to files.cgm_data to data.return() at the end.package_name:: to the individual functions used. To find which package a function comes from, use ?functionname to see the help documentation.R/functions.R file. Then go back to the docs/learning.qmd file and (making sure the old function is deleted), render again with Ctrl-Shift-KCtrl-Shift-K or with the Palette (Ctrl-Shift-PCtrl-Shift-P, then type “render”) to check that the function works after moving it.R/functions.R file with the Palette (Ctrl-Shift-PCtrl-Shift-P, then type “style file”).When you’re ready to continue, place the sticky/paper hat on your computer to indicate this to the teacher 👒 🎩

Quickly cover this and get them to do the survey before moving on to the discussion activity.

map() when you want to repeat a function on multiple items at once.list_rbind() to combine multiple data frames into one data frame by stacking them on top of each other.Time: ~6 minutes.

As we prepare for the next session and taking the break, get up and discuss with your neighbour or group the following questions:

This lists some, but not all, of the code used in the section. Some code is incorporated into Markdown content, so is harder to automatically list here in a code chunk. The code below also includes the code from the exercises.

cgm_files <- here("data-raw/dime/cgm/") |>

dir_ls(glob = "*.csv")

cgm_files

cgm_data <- cgm_files |>

map(import_dime)

cgm_data[1:2]

cgm_data <- cgm_files |>

map(import_dime) |>

list_rbind()

cgm_data

cgm_data <- cgm_files |>

map(import_dime) |>

list_rbind(names_to = "file_path_id")

cgm_data

#' Import all DIME CSV files in a folder into one data frame.

#'

#' @param folder_path The path to the folder that has the CSV files.

#'

#' @return A single data frame/tibble.

#'

import_csv_files <- function(folder_path) {

files <- folder_path |>

fs::dir_ls(glob = "*.csv")

data <- files |>

purrr::map(import_dime) |>

purrr::list_rbind(names_to = "file_path_id")

return(data)

}